When people think about World War II, they rarely think about chessboards. Yet the war didn’t just interrupt tournaments and scatter players across continents—it reshaped the entire ecosystem of modern chess. From secret codebreaking rooms to massive state-sponsored programs, the post-war chess world was built in the shadow of global conflict.

War rooms, codebreakers, and the chess mind

Chess and cryptography have always shared a natural bond: patience, pattern recognition, and the ability to think several steps ahead. During World War II, that overlap became literal.

At Bletchley Park, Britain’s codebreaking hub, several strong chess players worked on cracking German ciphers. Among them were:

- Conel Hugh O’Donel “Hugh” Alexander – British champion, later head of cryptanalysis sections

- Harry Golombek – British international master who also served as a wartime linguist and codebreaker

These men spent their days wrestling with Enigma traffic and their nights analyzing positions. After the war, both returned to chess and became influential figures—Golombek as an arbiter and writer, Alexander as a leading organizer and analyst. Their careers symbolized a new respect for chess as a discipline connected to intelligence work and analytical thinking, not just recreation.

The Soviet machine rises

No force changed modern chess more than the Soviet Union’s approach after the war.

Before World War II, chess was international but fragmented. Afterward, the USSR made a deliberate decision: chess would be a showcase of intellectual superiority. What followed was unprecedented:

- state-funded chess schools

- paid trainers and formal curricula

- systematic talent identification

- scientific study of openings and endgames

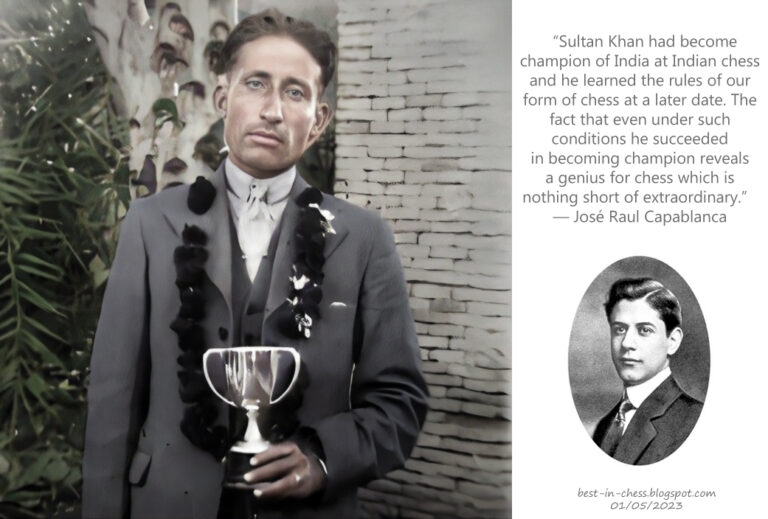

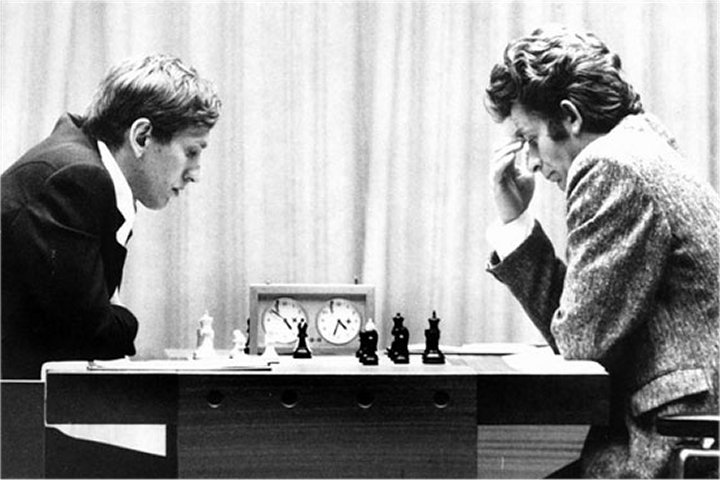

In 1948, after the death of world champion Alexander Alekhine, a special tournament was organized to determine a new champion. Mikhail Botvinnik, backed by rigorous Soviet preparation, won—and Soviet players would hold the world title (with one brief exception) until 1972. Botvinnik wasn’t just a champion; he was a symbol of planning, discipline, and state-backed training.

This era produced a dynasty: Smyslov, Tal, Petrosian, Spassky—all products of institutions created or expanded in the post-war period. Chess stopped being just an individual pastime and became a national project.

The U.S.–USSR rivalry begins

The war reorganized geopolitical power blocs, and chess followed the same map. One of the clearest symbols was the famous 1945 USA–USSR radio match. Teams faced each other across continents, transmitting moves electronically. The Soviet team won convincingly.

It was more than a match. It marked:

- the beginning of the Cold War rivalry on the chessboard

- recognition of Soviet dominance

- the realization in the West that casual training wouldn’t compete with a state system

From then onward, international tournaments were seen through political lenses. Chess became proxy competition, setting the stage for later showdowns—most famously Fischer–Spassky in 1972.

A fractured European chess world

While Soviet chess surged, the war devastated the traditional chess centers of Europe.

- Many players were displaced, imprisoned, or killed

- Clubs in Germany, Poland, and parts of Eastern Europe were destroyed

- Jewish masters—who had been central to pre-war chess—were especially affected

Brilliant careers were cut short. Whole local chess cultures vanished or had to rebuild from scratch. This loss shaped the post-war field: the Soviet Union faced a weakened rival landscape and filled the vacuum with organization and numbers.

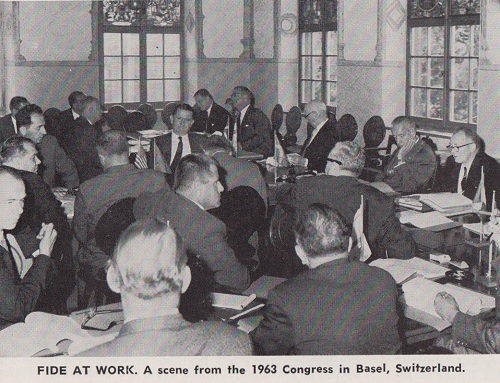

FIDE and the modern structure of chess

World War II also reshaped chess governance. Before the war, world championship arrangements were largely private—organized by players and sponsors. Afterward, the international federation FIDE emerged as the central authority.

Post-war developments included:

- formal cycles of Candidates’ and Interzonal tournaments

- standardized time controls and norms

- clearer title systems (International Master, Grandmaster)

Modern professional chess—circuits, titles, qualification systems—grew from structures solidified in the late 1940s and 1950s as the world reorganized itself.

The legacy we still live with

Many features players take for granted today are direct consequences of the war era:

- national training programs

- scientific opening preparation

- psychological and physical conditioning

- chess as a symbol of national prestige

Even online debates about “which country dominates chess” echo post-WWII narratives forged in the USSR versus the rest of the world dynamic.

World War II broke the old chess world and forced it to rebuild. What emerged was more organized, more professional, and deeply entangled with politics and technology. It’s no exaggeration to say that the modern era of grandmasters, databases, and structured titles stands on foundations poured in the 1940s.